Keynote Speaker

Keynote Speaker

Books

In the media

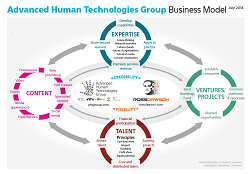

Business Model

Savvy sci-fi futurists: 21 science fiction writers who predicted inventions way ahead of their time

By Vanessa Cartwright

Many futurists, scientists and inventors have been inspired by the imagination and anticipation of the future inherent to science fiction novels. From the Internet to iPads to smart machines, some of the world’s greatest advances in technology were once fictional speculation. As sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke wrote in Profiles of the Future (1962), “The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.”

Sci-fi is a powerful genre because it envisages how society could function differently. “This is the first step towards progress as it allows us to imagine the future we want, and consider ways to work towards it,” writes physicist and philosopher Dr. Helen Klus. “It also makes us aware of futures we wish to avoid, and helps us prevent them.”

The 21 sci-fi futurists featured below gave some of the earliest recorded mentions of inventions that have since become a reality. Several of these authors doubted that their fictional inventions would ever come to fruition, or thought it would take much longer for their inventions to occur than it actually took. Others were remarkably spot on. Regardless of accuracy, however, what these future thinking authors all recognized was that change is an inevitable and powerful force that can blur the boundaries between fiction and possibility.

1. Rocket-powered space flight: Cyrano de Bergerac, 1657

While astronomer Johannes Kepler had envisaged lunar travel in his Somnium (The Dream) written in 1608, the idea was so strange at the time that Kepler chose to have demons transport his protagonist. In 1638, Bishop Francis Godwin had a similar flight of fancy: his protagonist in The Man in the Moone hitched a ride with migratory birds. But in The Other World: The States and Empires of the Moon, an early science-fiction story by French author Cyrano de Bergerac, the protagonist makes a machine that launches when soldiers fasten fireworks underneath it:

While astronomer Johannes Kepler had envisaged lunar travel in his Somnium (The Dream) written in 1608, the idea was so strange at the time that Kepler chose to have demons transport his protagonist. In 1638, Bishop Francis Godwin had a similar flight of fancy: his protagonist in The Man in the Moone hitched a ride with migratory birds. But in The Other World: The States and Empires of the Moon, an early science-fiction story by French author Cyrano de Bergerac, the protagonist makes a machine that launches when soldiers fasten fireworks underneath it:

“I ran to the Soldier that was giving Fire to it… and in great rage threw my self into my Machine, that I might undo the Fire-Works that they had stuck about it; but I came too late, for hardly were both my Feet within, than whip, away went I up in a Cloud.”

In a literary sense, this passage evokes the exhaust flames produced by rockets with internal combustion engines. The first rocket that propelled something into space—the satellite Sputnik—would be launched 300 years later, in 1957.

2. Submarines: Margaret Cavendish, 1666

Many people attribute the first mention of a submarine to Jules Verne, who described an electric submarine in his famous book 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1870). However, few people know that an early form of submarine was mentioned in The Description of a New World, Called The Blazing-World (1666), a book about a satirical utopian kingdom, written by Margaret Cavendish, the Duchess of Newcastle. The book is perhaps the only known work of utopian fiction by a woman in the 17th century, as well as one of the earliest examples of what we now call science fiction. Cavendish’s protagonist talks to sentient animals about various scientific theories, including atomic theory, before travelling home in a submarine when she hears that her homeland is under threat.

3. Machine-automated language: Jonathan Swift, 1726

Jonathan Swift, the well-known Irish satirist who wrote Gulliver’s Travels, critiqued the so-called scientific literature of his time, which was not always the result of rational thinking. Consequently, when Swift described an “engine” that could form sentences, he was satirizing the arbitrary methods of some of his scientific contemporaries:

“…the most ignorant person, at a reasonable charge, and with a little bodily labour, might write books in philosophy, poetry, politics, laws, mathematics, and theology, without the least assistance from genius or study”.

What Swift may not have realized was that his ensuing description of a machine containing all the words of the language spoken in Lagado, a fictional city, is one of the earliest known references to a device broadly representing a computer. Nowadays, computers are able to generate permutations of word sets, as Swift envisaged.

4. Eugenics: Nicolas-Edme Rétif, 1781

Sci-fi writers have had their share of scandal. One such writer was Nicolas-Edme Rétif de la Bretonne, a Frenchman whose work was still deemed licentious in 1911 by the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Despite Rétif’s notoriety, some critics now praise his inventions and naturalistic approach in his science fiction book La Découverte Australe par un Homme-Volant (The Discovery of Australasia by a Flying Man). As well as describing aviation gear two years before Louis-Sébastien Lenormand made the first recorded public parachute descent, Rétif converts early thoughts about evolution, adaptation and transformism into fiction.

Sci-fi writers have had their share of scandal. One such writer was Nicolas-Edme Rétif de la Bretonne, a Frenchman whose work was still deemed licentious in 1911 by the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Despite Rétif’s notoriety, some critics now praise his inventions and naturalistic approach in his science fiction book La Découverte Australe par un Homme-Volant (The Discovery of Australasia by a Flying Man). As well as describing aviation gear two years before Louis-Sébastien Lenormand made the first recorded public parachute descent, Rétif converts early thoughts about evolution, adaptation and transformism into fiction.

Among the creatures Rétif’s hero encounters is an articulate half-human, half-baboon. “The book is part natural history, part imaginary evolutionary experiment, in which Rétif brings these primitive beings to life and demonstrates the genetic mixing that gradually results in both the differentiation of animal species and the emergence of humankind,” writes Amy S. Wyngaard. Rétif imagined Australasia as a sort of eugenic utopia, a century before the term “eugenics” would be coined by Charles Darwin’s half-cousin, Francis Galton.

5. Oxygen in air travel and space travel: Jane Webb Loudon, 1828

A future where women wear trousers and automatons function as surgeons and lawyers was foreseen by pioneering sci-fi writer Jane Webb Loudon. In her book The Mummy: A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century, Loudon gave a very early mention of the notion that, to survive in outer space in earth’s orbit, it would be necessary to take some air with you. She wrote:

“… and the hampers are filled with elastic plugs for our ears and noses, and tubes and barrels of common air, for us to breathe when we get beyond the atmosphere of the earth.”

So, next time you are on an airplane watching a demo about oxygen masks, don’t forget to remember the contribution of Jane Webb Loudon!

6. Debit cards: Edward Bellamy, 1888

Edward Bellamy’s novel Looking Backward: 2000 to 1887 featured an American utopian society that used so-called “credit cards”. Bellamy’s concept actually relates more to debit cards and spending social security dividends than borrowing from a bank. The main character describes how people are given a stated amount of credit on their card to purchase goods from the public storehouses:

“You observe,” he pursued as I was curiously examining the piece of pasteboard he gave me, “that this card is issued for a certain number of dollars. We have kept the old word, but not the substance…The value of what I procure on this card is checked off by the clerk, who pricks out of these tiers of squares the price of what I order.”

Debit cards and credit cards would be invented more than 60 years later.

7. Electric fences: Mark Twain, 1889

A lesser-known fact about American novelist and humorist Mark Twain is that he predicted the electric fence. In his novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, Twain transports an American engineer back in time to the court of King Arthur, where modern engineering and technology win him fame as a magician. In one passage, Twain described the electric fence in considerable detail, before concluding that it has a marvellous use in defense:

A lesser-known fact about American novelist and humorist Mark Twain is that he predicted the electric fence. In his novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, Twain transports an American engineer back in time to the court of King Arthur, where modern engineering and technology win him fame as a magician. In one passage, Twain described the electric fence in considerable detail, before concluding that it has a marvellous use in defense:

“Now, then, observe the economy of it. A cavalry charge hurls itself against the fence; you are using no power, you are spending no money, for there is only one ground-connection till those horses come against the wire; the moment they touch it they form a connection with the negative brush through the ground, and drop dead.”

Electric fences were not used to control livestock in the United States until the early 1930s.

8. Videoconferencing: Jules Verne, 1889

Famous French sci-fi pioneer Jules Verne described the “phonotelephote”, a forerunner to videoconferencing, in his work In the Year 2889. The phonotelephote allowed “the transmission of images by means of sensitive mirrors connected by wires,” Verne wrote. This was one of the earliest references to a videophone in fiction, according to Technovelgy.com, a site that traces inventions and ideas from science fiction. In the Year 2889 also predicts newscasts, recorded news, and skywriting—inventions which have all come to fruition well before 2889.

9. X-ray and CAT scan technology: John Elfreth Watkins Jr., 1900

In a visionary article for the Ladies’ Home Journal entitled “What May Happen in the Next Hundred Years”, an American named John Elfreth Watkins Jr. made several remarkable predictions. One of the most striking was his prediction of X-ray and CAT scan technology:

“Physicians will be able to see and diagnose internal organs of a moving, living body by rays of invisible light.”

In the same article, Watkins also foresaw high-speed trains, satellite television, the electronic transmission of photographs, and the application of electricity in greenhouses.

10. Radar: Hugo Gernsback, 1911

The beauty of Hugo Gernsback’s prediction of radar lies in its intricate detail. The description occurs in Gernsback’s series of short stories, Ralph 124c 41+, which was a play on “One to Foresee For One Another” (and appears to have anticipated texting language as well):

The beauty of Hugo Gernsback’s prediction of radar lies in its intricate detail. The description occurs in Gernsback’s series of short stories, Ralph 124c 41+, which was a play on “One to Foresee For One Another” (and appears to have anticipated texting language as well):

“A pulsating polarized ether wave, if directed on a metal object can be reflected in the same manner as a light ray is reflected from a bright surface… By manipulating the entire apparatus like a searchlight, waves would be sent over a large area. Sooner or later these waves would strike a space flyer. A small part of these waves would strike the metal body of the flyer, and these rays would be reflected back to the sending apparatus. Here they would fall on the Actinoscope, which records only the reflected waves, not direct ones…From the intensity and elapsed time of the reflected impulses, the distance between the earth and the flyer can then be accurately estimated.”

In 1933, a working radar device that could detect remote objects by signals was created.

11. Atomic bomb: H.G. Wells, 1914

One of the most unfortunate legacies of science fiction is the genre’s inspiration for the atomic bomb. In The World Set Free, H.G. Wells predicted that a new type of bomb fuelled by nuclear reactions would be detonated in the 1956. It happened even sooner than he thought. Physicist Leó Szilárd apparently read Wells’s book and patented the idea. Szilárd was later directly involved in the Manhattan Project, which led to the tragedy of nuclear bombs being dropped on Japan in 1945. Strikingly, Wells spelled not only spelled out the idea of a sustained atomic reaction, he also predicted the moral and ethical horror that people would feel upon the use of atomic bombs, and the radioactive ruin that would last long after the bomb was dropped.

12. Cyborgs: E.V. Odle, 1923

The Clockwork Man by E.V. Odle depicted a cyborg as a major character and also helped to introduce steampunk. The Clockwork Man is a cyborg who suffers from a glitch that causes him to fall into the world of 1923. The book dealt with what happens to humanity when people merge with machines and live inside a vast cyberspace-like world that seems to offer them infinite plenitude. It wasn’t until 1972 that the cyborg concept gained greater currency, when Martin Caidin’s novel Cyborg speculated in depth about human-like bionic limbs. Today, cyborgs are becoming a reality.

The Clockwork Man by E.V. Odle depicted a cyborg as a major character and also helped to introduce steampunk. The Clockwork Man is a cyborg who suffers from a glitch that causes him to fall into the world of 1923. The book dealt with what happens to humanity when people merge with machines and live inside a vast cyberspace-like world that seems to offer them infinite plenitude. It wasn’t until 1972 that the cyborg concept gained greater currency, when Martin Caidin’s novel Cyborg speculated in depth about human-like bionic limbs. Today, cyborgs are becoming a reality.

Some readers believe that E.V. Odle was a pen name used by Virginia Woolf, who dabbled in science fiction and sought to protect her credibility as a serious writer. Most consider this an unfounded rumor, and hold that E.V. Odle was Edwin Vincent Odle, a little-known British playwright, critic, and author. Regardless of the author’s identity, Virginia Woolf’s work seems to have influenced the novel. Reviewer Annalee Newitz calls the book “an odd mashup of Virginia Woolf and H.G. Wells”.

13. In vitro fertilization: J.B.S. Haldane, 1924

J.B.S. Haldane was a British scientist who also imagined the future directions of biology in his book Daedulus; or Science and the Future. The work proclaimed how scientific revolution might alter the most private aspects of life, death, sex, and marriage. This was a bold move given the uproar that inventions like birth control were causing in contemporary media.

Haldane predicted the widespread practice of in vitro fertilization, what he called “ectogenesis”. His theory of reproductive technology and his scientific futurism influenced Aldous Huxley’s novel Brave New World (1932).

Haldane also stressed that humans need to make advances in ethics to match our advances in science. Otherwise, he feared, science would bring grief, not progress, to humankind.

14. Teleoperated robot surrogates: Manly Wade Wellman, 1938

The short story The Robot and the Lady by Manly Wade Wellman offered an early fictional account of teleoperated robots. The context is entertaining: roboticist Dr. Alvin Peabody seeks a date with another researcher in the field, Muriel Winthrop, but fears he is too “scrawny and fluffy-headed” to attract her. So he chooses his “tall, dashing” prize robot to speak and act for him. Ironically, Winthrop also chooses a robot surrogate to woo Peabody. When both parties discover the mutual deception, they believe they are made for one another and hasten to meet in person.

The short story The Robot and the Lady by Manly Wade Wellman offered an early fictional account of teleoperated robots. The context is entertaining: roboticist Dr. Alvin Peabody seeks a date with another researcher in the field, Muriel Winthrop, but fears he is too “scrawny and fluffy-headed” to attract her. So he chooses his “tall, dashing” prize robot to speak and act for him. Ironically, Winthrop also chooses a robot surrogate to woo Peabody. When both parties discover the mutual deception, they believe they are made for one another and hasten to meet in person.

Some robot surrogates already exist. See, for example, the Inmoov Robots for Good designed for hospitalized children, the InTouch medical rounding robot for doctors, and the Geminoid human replicas.

15. Microwavable heat-n-eat food: Robert Heinlein, 1948

In Space Cadet, famous sci-fi author Robert Heinlein took the newly invented microwave one step further by predicting the rise of ready-to-eat, microwavable food:

“Theoretically every ration taken aboard a Patrol vessel is pre-cooked and ready for eating as soon as it is taken out of freeze and subjected to the number of seconds, plainly marked on the package, of high-frequency heating required.”

It took a few decades before Heinlein’s vision became an everyday reality.

16. Earphones: Ray Bradbury, 1950

In Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury described earphones that were much more convenient than the huge headphones of his day:

“And in her ears the little seashells, the thimble radios tamped tight, and an electronic ocean of sound, of music and talk and music and talk coming in, coming in on the shore of her unsleeping mind.”

In-ear headphones were released to the mass market in 1980.

17. Machine intelligence outsmarting humans: Clifford Simak, 1951

In Time and Again (also published as First He Died), Clifford Simak depicted a chess game between a man and a robot:

“In the screen a man was sitting before a chess table. The pieces were in mid-game. Across the board stood a beautifully machined robotic.

The man reached out a hand, thoughtfully played a knight. The robotic clicked and chuckled. It moved a pawn…

“Mr. Benton hasn’t won a game in the past ten years…”

“… Benton must have known, when he had Oscar fabricated, that Oscar would beat him,” Sutton pointed out. “A human simply can’t beat a robotic expert.”

Simak’s early sci-fi reference of robots or computers being unbeatable at chess occurred four decades before futurist Ray Kurzweil predicted in The Age of Intelligent Machines that a computer would beat the best human chess players by 2000. In 1997, sure enough, IBM’s “Deep Blue” beat Garry Kasparov.

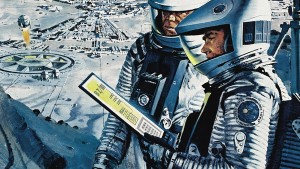

18. iPad: Arthur C. Clarke, 1968

The “newspad” conceived in Arthur C. Clarke’s novel and film 2001: A Space Odyssey has been realized in the iPad, albeit with a greater variety of functions. Clarke wrote:

The “newspad” conceived in Arthur C. Clarke’s novel and film 2001: A Space Odyssey has been realized in the iPad, albeit with a greater variety of functions. Clarke wrote:

“When he tired of official reports and memoranda and minutes, he would plug in his foolscap-size newspad into the ship’s information circuit and scan the latest reports from Earth. One by one he would conjure up the world’s major electronic papers…Switching to the display unit’s short-term memory, he would hold the front page while he quickly searched the headlines and noted the items that interested him. Each had its own two-digit reference; when he punched that, the postage-stamp-size rectangle would expand until it neatly filled the screen and he could read it with comfort. When he had finished, he would flash back to the complete page and select a new subject for detailed examination…”

19. Electric cars: John Brunner, 1969

Perhaps one of the most prophetic novels ever, John Brunner’s novel Stand on Zanzibar, set in 2010, creates an America under the leadership of President Obomi, plagued by school shootings and terrorist attacks. The EU is in existence, major cities like Detroit become impoverished, tobacco faces backlash but marijuana is decriminalised, and gay and bisexual lifestyles have gone mainstream. The inventions used in society include on-demand TV, laser printers, and electric cars. Brunner believed these cars would be powered by rechargeable electric fuel cells, much as they are today, and that Honda would be a leading manufacturer. Recently, Honda has affirmed that its electric vehicles are a “core technology”.

20. Real-time translation: Douglas Adams, 1979

The amusing little Babel Fish in Adams’ renowned The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy brings real-time translation to Arthur Dent and his fellow characters. Several apps now on the market for Android or iOS mimic the Babel Fish’s abilities. One of these apps is Lexifone, which translates from one language to another when someone speaks during a call. Microsoft has also been developing real-time translation for Skype.

21. The ubiquity of the World Wide Web: David Brin, 1990

Brin’s famous book Earth made several remarkable predictions, inspiring fans to monitor its success rate. One of the most prominent and important of these predictions was the ubiquity of the World Wide Web, in a decade where the Web was still new and uncertain. “In EARTH, I portrayed my 21st-century characters using screen displays filled with clickable links—in other words, Web pages,” Brin told PopMech. “As it turned out, Marc Andreessen and Tim Berners-Lee had similar ideas at the same time and were plugging away at changing the real world, making possibilities come true for everyone.”

Brin’s famous book Earth made several remarkable predictions, inspiring fans to monitor its success rate. One of the most prominent and important of these predictions was the ubiquity of the World Wide Web, in a decade where the Web was still new and uncertain. “In EARTH, I portrayed my 21st-century characters using screen displays filled with clickable links—in other words, Web pages,” Brin told PopMech. “As it turned out, Marc Andreessen and Tim Berners-Lee had similar ideas at the same time and were plugging away at changing the real world, making possibilities come true for everyone.”

The ongoing role of sci-fi

As futurist Ross Dawson has observed, “Fiction about the future whets our appetite for new technologies. It is how we discover what it is we truly want, driving new developments.”

As the pace of change continues to increase, a statement by scientist and sci-fi author Isaac Asimov rings truer than ever: “It is change, continuing change, inevitable change, that is the dominant factor in society today. No sensible decision can be made any longer without taking into account not only the world as it is, but the world as it will be.”

Science fiction writers foresee the inevitable. They inspire us to turn fiction into reality, but they also remind us to reflect on the consequences of our actions and remember what is most important to humanity.

Image sources: Steve Jurvetson, Gallica Bibliothèque Numérique, Hannah Banner, U.S. Naval Forces Central Command, George Boyce, Sebastian Dooris, us vs th3m, and SEO